A Monstrous Courtship | قطعهای از بهمننامهی ایرانشاه بن ابی الخیر

Introduction to the Text

Likely completed between 1092 and 1108 CE, the Bahmannāma (“Book of Bahman”) is the work of a poet so obscure that even his name is not certain. Though there is a general consensus around the form Irānshāh ebn-e Abi-l-Khayr, the first element is spelled “Irānshān” or even “Inshān” in some manuscripts. Dedications in the text to the Seljuq sultans Nāser ad-Din Mahmud ebn-e Malekshāh and Ghiyās ad-Din Mohammad ebn-e Malekshāh position him within the Seljuq Empire around the turn of the 12th century CE.

Irānshāh is credited with another epic work, the Kushnāma (“Book of Kush”). Both of the poems offer revisionist takes on the New Persian epic tradition established by the monumental Shāhnāma (“Book of Kings,” 1010 CE) of Abolqāsem Ferdowsi. This Book drew upon Persian legend, Zoroastrian religious tradition, and Arabic historiography to craft an immense saga of Iran’s pre-Islamic past, from the first king Gayomart down to the Muslim conquests of the 7th century CE. Subsequent epic poets adopted the Shāhnāma’s meter and diction, often situating their narratives in gaps within the earlier poem’s millennia-long scope—a practice literalized by later scribes, who often incorporated segments of these poems seamlessly into Shāhnāma manuscripts.

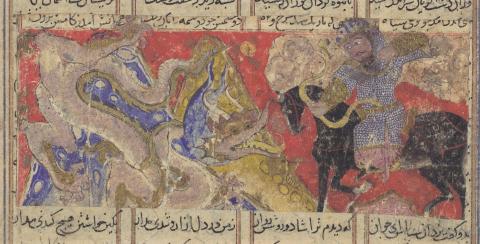

In the Bahmannāma, Irānshāh centers not the usual epic heroes but rather a villain, the tyrannical King Bahman. Known for his bloody vengeance against the family of the Sistāni champion Rostam, Bahman is an overbearing, homicidal tyrant. Frequently defeated in battle, he is ultimately devoured by a serpentine monster, an azhdahā, making him the only epic character who fails to overcome such a beast.

Before this shocking finale, however, the poem features another encounter with an azhdahā. In this excerpt, the hero Borzin-Āzar (“Exalted Flame,” usually just called Borzin), son of Farāmarz (“Beyond-the-Border”), and grandson of Rostam, takes a break from his struggle against Bahman. Together with his companions, Marzbān (“Margrave”) and Tokhāra (“The Tokharian”), he sets out on a hunting expedition. Along the way, they encounter a lion-hunting youth who directs them to a large nomadic encampment with abundant livestock. The lord of the herds is Burāsp, who in the course of a lavish welcome feast reveals that the lion-hunting youth is his daughter. This warrior maiden will only marry the man who can overcome her father’s champion wrestler, a Black African man (zangi), and then defeat her in a joust. Borzin accomplishes these feats, but before the wedding, Burāsp reveals the reason behind this warlike courtship. Every year, he is forced to deliver his daughter up to a sexually rapacious cloud; if he fails, his livestock will be slaughtered. Horrified, Borzin witnesses this ritual. He then pursues the cloud back to its mountain lair, where it reveals itself as a monstrous beast. Borzin kills it, and the excerpt ends with a celebratory feast at the court of Burāsp’s brother, the king of Pārs.

Violence and eroticism entwine throughout this passage. One key word is azhdahā, a chimeric reptilian beast with anthropomorphic qualities, translated here as “dragon.” This first appears in this edition’s line 111, as a metaphor for the warrior princess; then, in 204, it describes Borzin as he overcomes her. These figurative usages are juxtaposed against the literal monster which terrorizes the young woman and her kingdom, itself killed by one final azhdahā—Borzin’s sword.

Irānshāh’s poetry invests in depictions of alterity that are both denigrated and desired. The African wrestler is a key figure in this project. Denied dialogue or even a name, his portrayal is a stark example of the anti-Blackness prevalent in Persian epic literature. He exists only to be overcome, even if the text here tacitly endorses Borzin’s chivalrous smackdown over Tokhāra’s outspoken bigotry. Yet verbal echoes link all of these figures—Borzin, the princess, the wrestler, and the monster. All are enmeshed in economies of violence that complicate simplistic narratives of culture heroes triumphing over the forces of chaos.

Neither of Irānshāh’s epics have been translated into English or other European languages, and scholarly discussion of them remains scant.

Introduction to the Source

The text transcribed here is not medieval; rather, it is a lithograph produced in Mumbai in 1907. This is one of at least two lithographed poems—the other being a Farāmarznāma, narrating the exploits of Borzin’s father—produced under the direction of Rostam Pur-e Bahrām Sorush-e Tāfti. Sorush-e Tāfti was an Indian Parsi who traveled throughout India and Iran in search of antique manuscripts relating to the Sistāni heroes. According to Rahim ‘Afifi, editor of the only scholarly edition of the Bahmannāmeh, the lithograph is primarily based on an otherwise unidentified manuscript from 1667. At least four other manuscripts are known, the earliest dated to 1397-98 CE.

About this Edition

I have followed the lithograph wherever possible, only amending or supplying lines from ‘Afifi’s edition when the lithograph’s version is clearly garbled, or important passages are missing. These lines are marked with an asterisk [*] and underlined. No attempt has been made to preserve the original’s rhyme scheme (masnavi: AA, BB, CC, …xx) or meter (motaqāreb: ˘- - / ˘ - - / ˘ - - / ˘ - ). I have generally opted for a more naturalistic style over literal renditions. Certain pronouns have been replaced with proper names to aid clarity. Culturally specific terms (gholām, azhdahā, div, zangi, etc.) have been rendered into rough English equivalents (“youth,” “dragon,” “demon, “African,” etc.), though I acknowledge this approach sacrifices important nuances for readability.

Thank you to Alexandra Hoffmann, Franklin Lewis, and Mary Thaler for numerous helpful suggestions and amendations.

Further Reading

Hanaway, W. L. “Bahman-Nāma.” Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. 2, no. 5, 2011, pp. 499-500.

- Brief scholarly outline of the epic.

Kuehn, Sara. The Dragon in Medieval East Christian and Islamic Art. Brill, 2011.

- Thorough discussion of the pre-modern Islamicate dragon, from an art-historical perspective.

van Zutphen, Marjolijn. Farāmarz, the Sistāni Hero: Texts and Traditions of the Farāmarznāme and the Persian Epic Cycle. Brill, 2014.

- Extensive survey of the Persian epic tradition after the Shāhnāma.

Sorush-e Tāfti, Rostam Pur-e Bahrām, ed. Bahmannāmeh. Matba’i-Fayzrasān, 1325 [1907].

- Lithograph copy of the source.

Irānshāh ebn-e Abi-l-Khayr. Bahmannāmeh. Edited by Rahim ‘Afifi. Enteshārāt-e ‘Elmi va Farhangi, 1380 [2001-2002].

- Published edition of the text.

Credits

Translation by Sam LasmanTranscription by Sam LasmanEncoded in TEI P5 XML by Danny SmithSuggested citation: Hakim Irānshāh ebn-e Abi-l-Khayr. "A Monstrous Courtship." Trans. Sam Lasman. Global Medieval Sourcebook. http://sourcebook.stanford.edu/text/monstrous-courtship. Retrieved on April 23, 2024.