Transcription by Leonardo Grao Velloso .

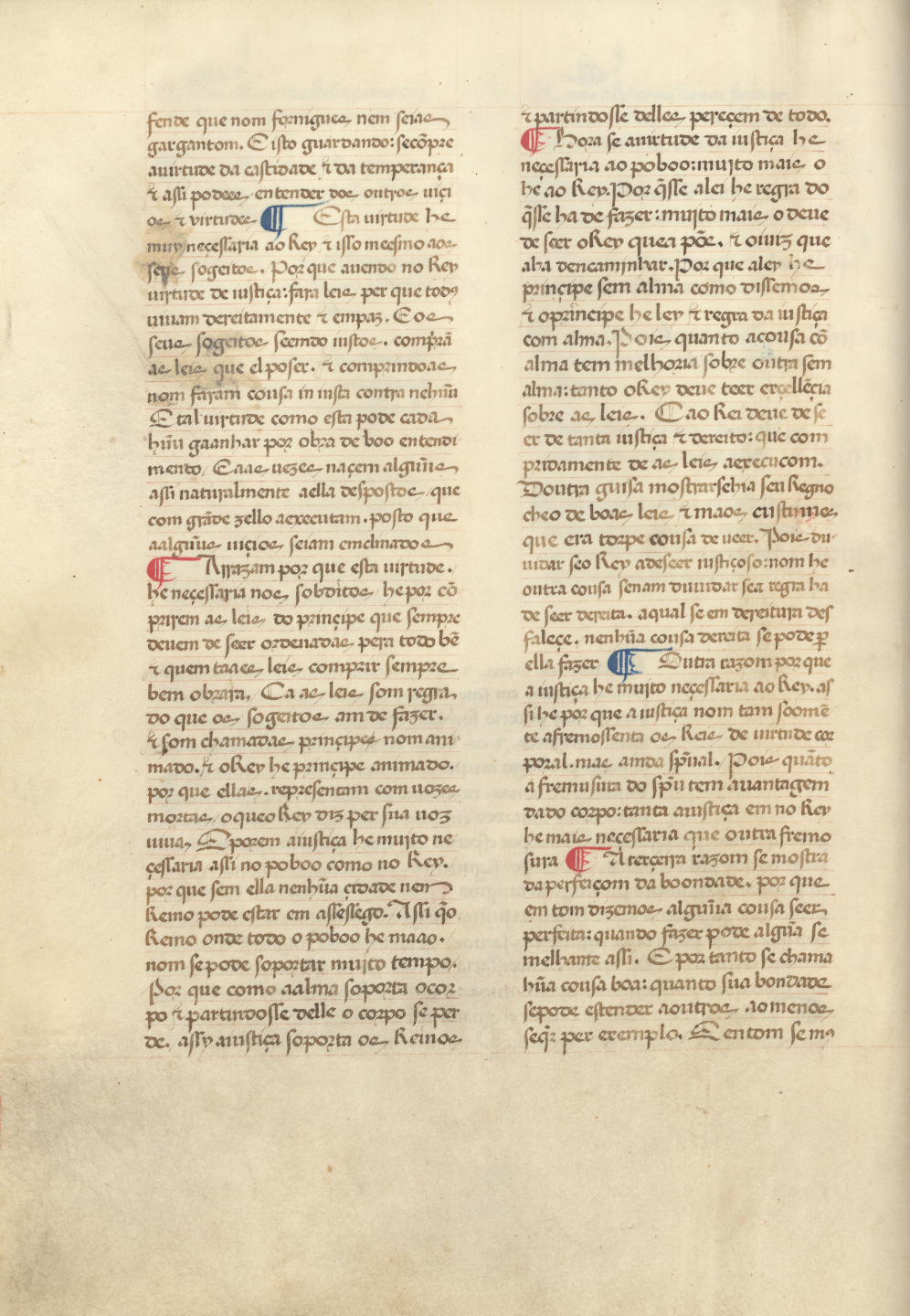

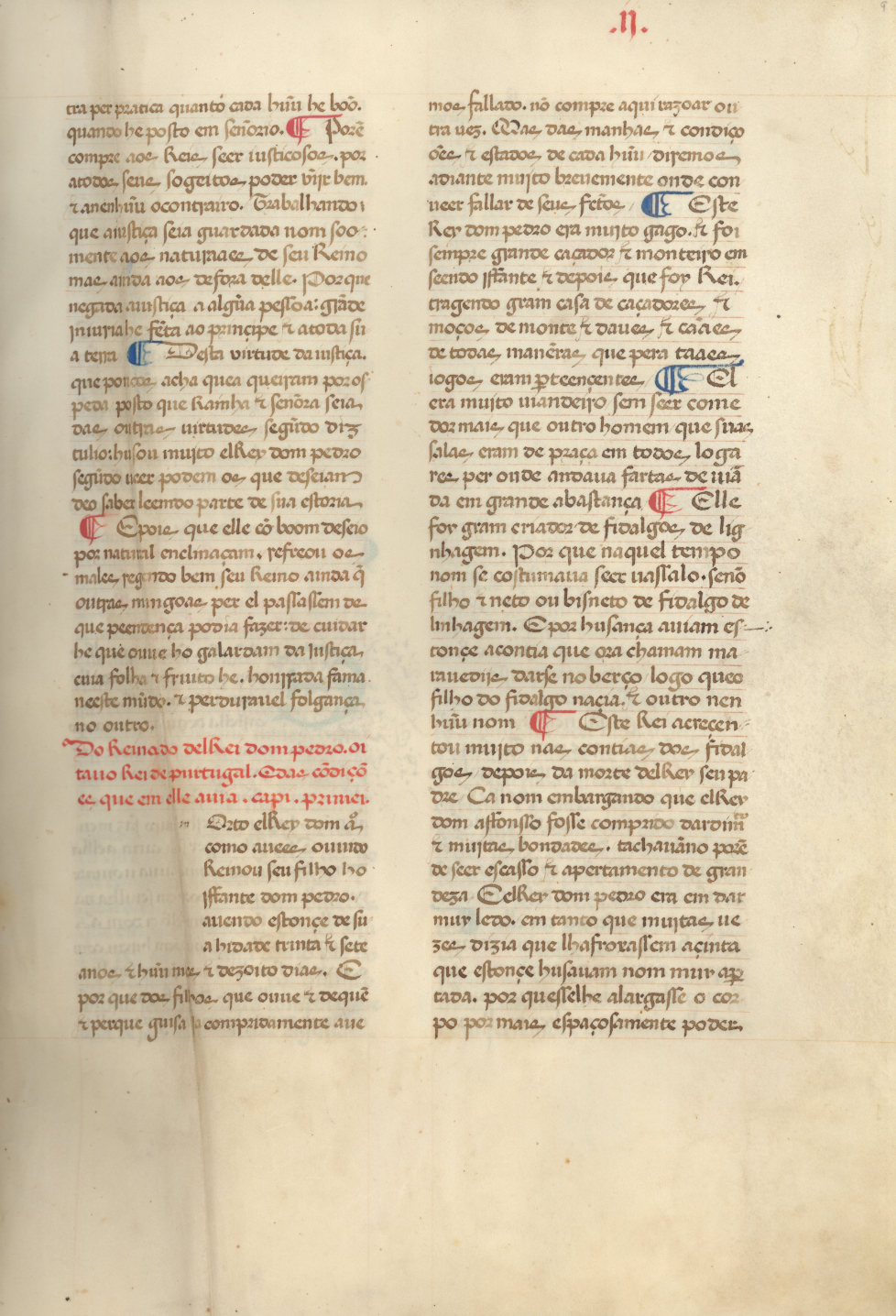

Chronica del Rey D. Pedro [Prologo] | Chronicle of King Peter I [Prologue]

Chronica del Rey D. Pedro [Prologo] | Chronicle of King Peter I [Prologue]

by Fernão Lopes

Text Source:

Bibliotheca Nacional de Portugal MS IL. 123, ff. 1r-2r.

Responsibility Statement:

- Transcription by Leonardo Grao Velloso

- Translation by Leonardo Grao Velloso

- Encoded in TEI P5 XML by Mae Velloso-Lyons

Editorial Principles:

Transcriptions and translations are encoded in XML conforming to TEI (P5) guidelines. The original-language text is contained within <lem> tags and translations within <rdg> tags.

Texts are translated into modern American English with maximum fidelity to the original text, except where it would impair comprehension or good style. Archaisms are preserved where they do not conflict with the aesthetic of the original text. Scribal errors and creative translation choices are marked and discussed in the critical notes.

Publication Details:

Published by Global Medieval Sourcebook.

The Global Medieval Sourcebook is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Scholars say that this strange beginning, referencing another text in which Lopes would have already presented a discussion about the definitions of justice, points to the existence of another prologue, possibly a prologue to a lost chronicle that he might have written before writing the Chronicle of Peter I, or another prologue to this same chronicle.

The Portuguese original, desvairadas guisas, implies a sense that the writings are disorganized, unreasonable for not having a logic. Desvairada/o means “that which lost its way.” This way of writing anticipates the next argument, against invention as a proper way of explaining justice. Fernão Lopes promises to tread paths already taken by previous writers, but in a more systematic way than the ones he criticizes.

The argument behind this image is very illuminating, as Fernão Lopes frames his work as a writer who collects ditos (sayings) from other writers, as opposed to framing himself as an inventor of a new concept or way of explaining justice. Arguments that ascribe authority to previous writers were very common in late medieval historical writing.

See first note.

Lopes is here referring back to the sentence where he says he is writing “as collectors who collect sayings from some writers.” Emphasizing an important point through referring back to it in the text was very common among chroniclers and writers of long prose. The emphasis is that Lopes is not inventing a classification of justice, but collecting real examples and presenting them together as an explanation of the idea of justice that he found in authoritative sources.

This statement seems to paraphrase the ten commandments (see Exodus 20:1-17), but, in fact, neither of these commands are included among the ten.

This argument about perfection as the attribute of that which can make something in its own likeness recalls Neo-Platonic theology about the idea of god as beautiful and good. Just as god can make beautiful and good things because he is perfect, so does the goodness of the king may extend to his subjects because goodness itself is perfect.

Marcus Tully Cicero (106 B.C.E – 43 B.C.E), Roman statesman, orator, consul, and philosopher.

Scholars say that this strange beginning, referencing another text in which Lopes would have already presented a discussion about the definitions of justice, points to the existence of another prologue, possibly a prologue to a lost chronicle that he might have written before writing the Chronicle of Peter I, or another prologue to this same chronicle.

The Portuguese original, desvairadas guisas, implies a sense that the writings are disorganized, unreasonable for not having a logic. Desvairada/o means “that which lost its way.” This way of writing anticipates the next argument, against invention as a proper way of explaining justice. Fernão Lopes promises to tread paths already taken by previous writers, but in a more systematic way than the ones he criticizes.

The argument behind this image is very illuminating, as Fernão Lopes frames his work as a writer who collects ditos (sayings) from other writers, as opposed to framing himself as an inventor of a new concept or way of explaining justice. Arguments that ascribe authority to previous writers were very common in late medieval historical writing.

See first note.

Lopes is here referring back to the sentence where he says he is writing “as collectors who collect sayings from some writers.” Emphasizing an important point through referring back to it in the text was very common among chroniclers and writers of long prose. The emphasis is that Lopes is not inventing a classification of justice, but collecting real examples and presenting them together as an explanation of the idea of justice that he found in authoritative sources.

This statement seems to paraphrase the ten commandments (see Exodus 20:1-17), but, in fact, neither of these commands are included among the ten.

This argument about perfection as the attribute of that which can make something in its own likeness recalls Neo-Platonic theology about the idea of god as beautiful and good. Just as god can make beautiful and good things because he is perfect, so does the goodness of the king may extend to his subjects because goodness itself is perfect.

Marcus Tully Cicero (106 B.C.E – 43 B.C.E), Roman statesman, orator, consul, and philosopher.

Scholars say that this strange beginning, referencing another text in which Lopes would have already presented a discussion about the definitions of justice, points to the existence of another prologue, possibly a prologue to a lost chronicle that he might have written before writing the Chronicle of Peter I, or another prologue to this same chronicle.

The Portuguese original, desvairadas guisas, implies a sense that the writings are disorganized, unreasonable for not having a logic. Desvairada/o means “that which lost its way.” This way of writing anticipates the next argument, against invention as a proper way of explaining justice. Fernão Lopes promises to tread paths already taken by previous writers, but in a more systematic way than the ones he criticizes.

The argument behind this image is very illuminating, as Fernão Lopes frames his work as a writer who collects ditos (sayings) from other writers, as opposed to framing himself as an inventor of a new concept or way of explaining justice. Arguments that ascribe authority to previous writers were very common in late medieval historical writing.

See first note.

Lopes is here referring back to the sentence where he says he is writing “as collectors who collect sayings from some writers.” Emphasizing an important point through referring back to it in the text was very common among chroniclers and writers of long prose. The emphasis is that Lopes is not inventing a classification of justice, but collecting real examples and presenting them together as an explanation of the idea of justice that he found in authoritative sources.

This statement seems to paraphrase the ten commandments (see Exodus 20:1-17), but, in fact, neither of these commands are included among the ten.

This argument about perfection as the attribute of that which can make something in its own likeness recalls Neo-Platonic theology about the idea of god as beautiful and good. Just as god can make beautiful and good things because he is perfect, so does the goodness of the king may extend to his subjects because goodness itself is perfect.

Marcus Tully Cicero (106 B.C.E – 43 B.C.E), Roman statesman, orator, consul, and philosopher.