The Legend of the Damsel Carcayçiona | ءَالْرَاكُنْتَمِيانْتُ دَا لَذُنْزَالّ كركيسينُ

Introduction to the Text

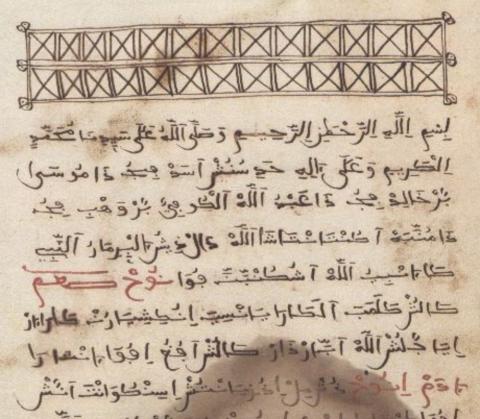

The Legend of the Damsel Carcayçiona is one of seven tales contained in an untitled manuscript compiled in 1587 and discovered in Almonacid de la Sierra, Spain, in 1884. A cross between a saint’s life and a description of paradise and hell, the story tells of a young princess who finds faith in Islam. The authorship is unknown.

The narrative follows a princess on a religious journey: a born idolator, she learns about Islamic religious practice and belief from a divine bird. Facing political exile, the damsel finds romantic love and religious enlightenment. The text moves between intricate descriptions of the afterlife, dialogue rich in both humor and tragedy, and creative plot twists. One stylistic feature to note is the text’s frame narration: the oral storytellers interject throughout the text.

The body of research on this text is relatively small, so there are potentially undiscovered interpretations and intertextual connections. The text addresses important themes--gender roles, religious conversion, patriarchy, martyrdom, romantic love, and political power--and has tremendous potential for enhancing our understanding of 16th-century Spain, specifically the Moorish presence in Spain post-Inquisition.

Introduction to the Source

The manuscript is now housed at the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) in Madrid. It contains Islamizations of Biblical stories, such as those of Noah and Jesus, as well as Islamic folklore. The manuscript’s orthography is Semitic, very nearly Arabic, but its semantics are of a Spanish derivative called Aragonese. This language, called Aljamiado from the Arabic “الهمجي”which loosely translates to “stranger” or “alien,” derives from the medieval union of Arabic and Latin influences in Europe. Arabic rule and influence on the Iberian peninsula began in the early 8th century and lasted roughly 700 years, a civilization to which scholars now refer as “Al-Andalus.” This heterogenous region produced artistic and linguistic crossovers between Latin and Semitic traditions until the Spanish Reconquista of 1492. After the Reconquista and Inquisition in 1492 and the ensuing Catholic rule, Semitic traditions, including religion and corresponding orthography, were banned altogether. This manuscript, dated to 1587, would not have been widely circulated, as its writing and subject were forbidden.

About this Edition

The presentation in the Global Medieval Sourcebook contains two witnesses, including a transcription in modern Arabic script and a translation into English. Because Arabic and Spanish do not have an exact phonetic-alphabetic makeup, there are some letters that serve only as representations of Spanish sounds (e.g. “e” as in “en”) and are represented with Arabic script, though they do not exist as independent letters in modern Arabic. Transcription practice has been to maximize clarity from the modern perspective without losing meaning, and as such, words and sentences have been broken up according to Spanish semantics. In other words, the text has been broken up retroactively into sentences that fit English syntactical convention. This is not always the case for articles, which may or may not be attached depending on the language of the word they’re describing, or the context in which they’re used. For example, Islamic words have their articles attached, as is customary in Arabic, whereas Spanish words generally have their articles detached.

The source of the transcription is Manuscript Junta 57 of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) in Madrid. A digitization of this manuscript can be viewed here.

Further Reading

Wacks, David. “Cultural Exchange in the Literatures and Languages of Medieval Iberia.” David A. Wacks, 30 Oct. 2013, davidwacks.uoregon.edu/tag/aljamiado/.

-

This piece, similar to Perry's, contextualizes the socio-cultural environment in which “The Legend of the Damsel Carcayçiona” was written.

Guillén Robles, Francisco. Leyendas moriscas sacadas de varios manuscritos existentes en las Bibliotecas Nacional, Real, y de D. P. de Gayangos, 3 vols. M. Tello, 1885.

-

Includes a translation of the text into Spanish.

Perry, Mary Elizabeth. The Handless Maiden: Moriscos and the Politics of Religion in Early Modern Spain. Princeton UP, 2005.

-

Perry outlines the parallels between “The Legend of the Damsel Carcayçiona” and “The Handless Maiden,” a fairytale with iterations in different cultures and epochs, and demonstrates how the former speaks to the Morisco experience in Spain in the late 16th century.

Boumehdi, Touria. “Una Miscelánea Aljamiada Narrativa y Doctrinal.” Institución Fernando El Católico, https://ifc.dpz.es/publicaciones/ebooks/id/3232, pp. 258-272.

-

A transcription of the manuscript in Latin characters.

Credits

Transcription by Jorden Rosen-Kaplan, and Donald WoodTranslation by Jordan Rosen-Kaplan, and Donald WoodEncoded in TEI P5 XML by Danny SmithSuggested citation: Anonymous. "The Legend of the Damsel Carcayçiona." Trans. Jordan Rosen-Kaplan and Donald Wood. Global Medieval Sourcebook. http://sourcebook.stanford.edu/text/legend-damsel-carcay%C3%A7iona. Retrieved on April 18, 2024.