Muspilli | Muspilli

Introduction to the Text

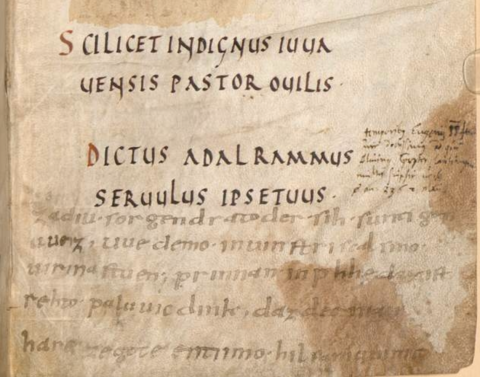

Muspilli is an incomplete verse narrative (103 lines) written in Old High German. The manuscript containing the poem, which was produced in Bavaria (southern Germany) in the 9th century CE, contains neither the beginning nor the end of the poem. The reason for its incompleteness is probably due to its having been written in the margins of another text: a Latin theological work composed by Adalram (d. 836), bishop of Salzburg, for the young Louis the German (ca. 810–876). It appears Muspilli was added to the manuscript later by a different scribe, but little can be deduced about who produced the text or why. It is conjectured that the beginning and end have been lost because they would have been written on the outermost pages of the manuscript, which often incur the most damage over time. One of the most debated questions about Muspilli is its name. The original manuscript does not include a title, and the name Muspilli was assigned by the poem's first editor, Johann Andreas Schmeller. The name comes from the Old High German word muspille, meaning the destruction of the world by fire, which occurs in line 57 of the poem. This is the only known occurrence of this word. Scholars have since tried to give it various names which better suit the purpose of the poem, but none of these has stuck.

Muspilli mainly deals with two main ideas: the fate of human souls after death and the Final Judgement. The first part of the poem describes how two groups of angels will fight over one soul to see whether it belongs in Heaven or Hell. The second part of the poem provides two narratives: Elijah and the Antichrist fight each other, the former as the champion of God and the latter as the champion of the Devil. In this duel, the Antichrist will be defeated and Elijah will be wounded and his blood will burn the whole world. Then the text describes how, in the Final Judgement, angels and demons will testify to the actions of humans on earth, and those actions will be scrutinized. At the end of the poem, the Holy Cross is brought forth and Christ reveals the wounds that he suffered for the sake of humankind.

One of the most discussed aspects of this poem are its sources. Although explicitly Christian elements are abundant, scholars have argued that Muspilli is deeply infused with pre-Christian culture and draws much of its material from Norse mythology. Although the names mentioned in the poem are all Christian figures, some scholars argue that they are essentially the Christian representation of Norse gods.

Muspilli is considered to be one of the most significant pieces of Old High German literature because of its vivid depiction of Christian themes in the vernacular language. Through this poem, modern readers can gain a better insight into the spiritual life and broader culture of ninth-century Germans.

Further Reading

Murdoch, Brian. “The Carolingian Period and the Early Middle Ages (750–1100).” The Cambridge History of German Literature, edited by Helen Watanabe-O'Kelly. Cambridge UP, 1997, pp. 1–39.

- An overview of German literature from 750-1100 CE which includes discussion of Muspilli (on pp. 24).

Wells, Christopher. "The Shorter German Verse Texts." German Literature of the Early Middle Ages, edited by Brian Murdoch, Camden House, 2004, pp. 157-199.

- An overview of Old High German verse texts, including a comparison between the Wessobrunn Prayer, Muspilli, and Lay of Ludwig (all published in the Global Medieval Sourcebook).

Credits

Transcription based on Althochdeutsche Literatur. Mit altniederdeutschen Textbeispielen. Auswahl mit Übertragungen und KommentarTranslation by Hannah FrakesIntroduction by Runqi ZhangEncoded in TEI P5 XML by Hannah FrakesSuggested citation: Anonymous. "Muspilli." Trans. Hannah Frakes. Global Medieval Sourcebook. http://sourcebook.stanford.edu/text/muspilli. Retrieved on April 23, 2024.